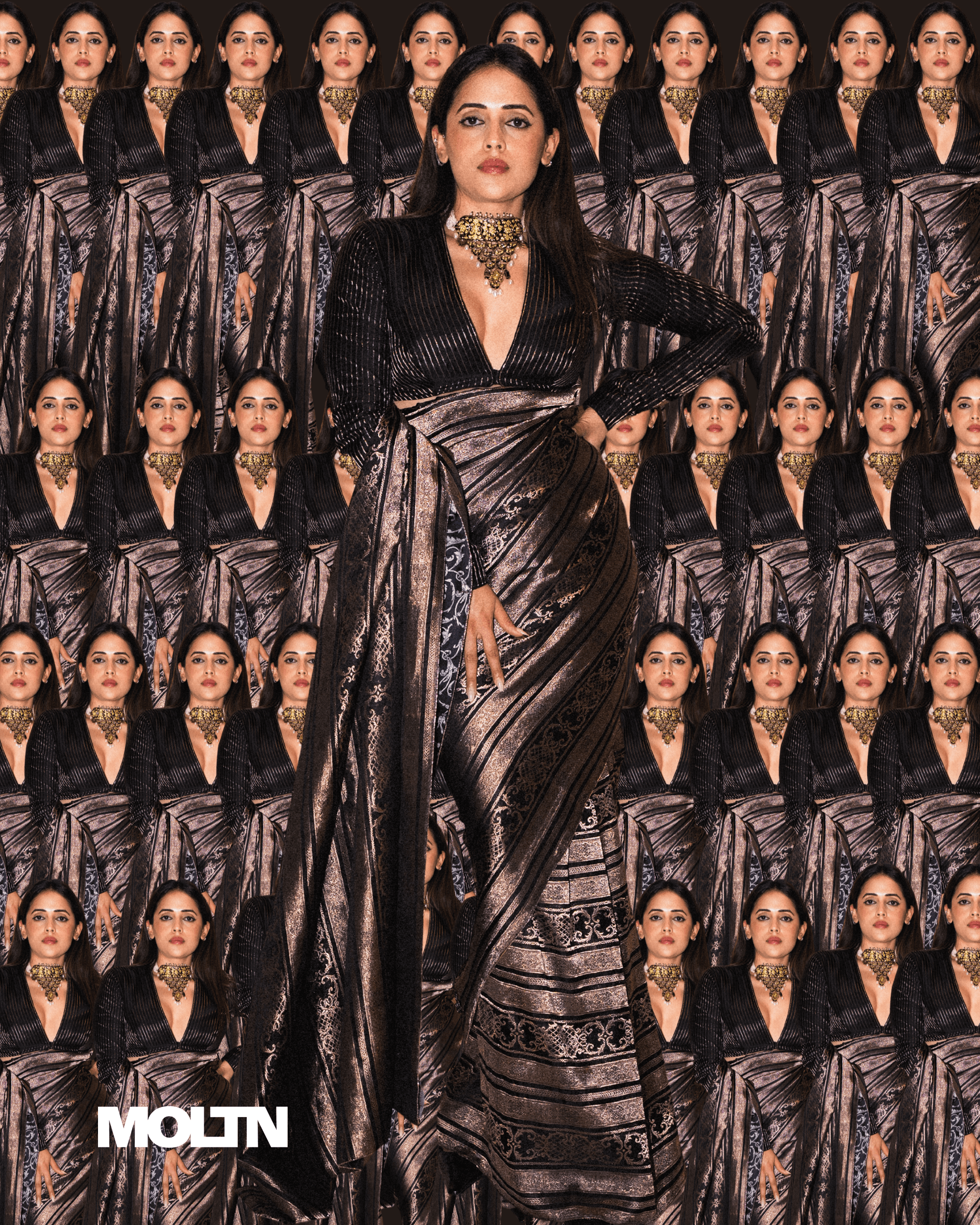

The Sari, Untied: Palak Shah on Freedom, Fabric, and Form

Style

•

January 2, 2026

Amrita Singh

Chief Editor

The Sari, Untied: Palak Shah on Freedom, Fabric, and Form

Style

•

January 2, 2026

Amrita Singh

Chief Editor

The sari was never something Palak Shah discovered - it was something she grew up inside. Surrounded by Banarasi weaving and generations of craftsmanship, her relationship with the garment was formed through touch, memory, and daily life. Today, her approach isn’t about rewriting tradition, but about letting the sari exist with ease - shaped by the wearer, the moment, and modern life.

For Palak Shah, the sari was never a fashion statement first - it was an environment. Growing up visiting Banaras, surrounded by looms, artisans, and generations of weaving knowledge, the sari existed as something lived-in and tactile long before it became something worn. Threads, scraps of fabric, the rhythm of handcraft - these were part of her everyday vocabulary.

That intimacy with the sari is what makes Palak’s approach feel quietly radical. Through Ekaya Banaras, she hasn’t tried to reinvent the garment - she’s simply given it room to breathe and revolutionised the relationship a modern generation has with the ancient garment. By stripping away rigid ideas of how a sari should look or be worn, she’s allowed a new generation to meet it on their own terms: fluid, expressive, and deeply personal.

In this conversation, Shah reflects on growing up inside a craft, losing and rediscovering her connection to it, and what it means to honour tradition not by preserving it unchanged - but by letting it evolve.

What’s your earliest memory of a sari - not as fashion, but as something you saw, touched, or were surrounded by growing up?

My earliest memories of a sari aren’t about fashion at all, they’re about growing up around them. I come from a family that has been involved in Banarasi saris and weaving for generations, so saris were always part of my everyday world. I remember going with my father into the narrow lanes of Banaras, walking past looms, watching artisans at work, and seeing a sari come to life thread by thread. I was especially drawn to the small fabric scraps left behind. I’d collect them and turn them into little dolls, stitching tiny outfits and creating my own imaginary worlds. That tactile connection: touching, playing, creating was probably my first real relationship with a sari.

Was there ever a moment when you personally didn’t feel connected to the sari - and if so, what changed that for you?

There was a time when I didn’t feel connected to the sari at all. I found it cumbersome, restrictive, almost distant from who I was becoming. I think that happened before I had really found my personal style, when I was still navigating what I genuinely liked versus what I felt I was supposed to like. There was a particularly clear moment I remember: walking into my own store and feeling disconnected, even thinking, I don’t like anything here. At that point, I was surrounded by very traditional saris, and while I respected them deeply, they didn’t feel like me yet. What changed everything was getting involved in the design process.

"I started creating saris the way I wanted to wear them, with a sense of ease and individuality. That’s when the sari slowly became mine."

Not something I was inheriting, but something I was actively shaping. Once I began designing for myself, the relationship shifted. The sari stopped feeling heavy and started feeling expressive. And that’s when I truly reconnected with it.

You’ve revolutionised the saree and helped make it feel wearable for a new generation. How did you have to unlearn the “rules” around wearing one?

Honestly, I don’t believe there were ever any rules to begin with. The biggest unlearning for me was simply realising that there are no rules when it comes to wearing a sari. Somewhere along the way, we’ve placed so much pressure on it: the number of pleats, how the pallu should fall, what’s considered the “right” way to drape it. At its core, a sari is just a piece of fabric, and fashion has always been about self-expression. It’s meant to be played with, experimented with, and enjoyed. You should drape it the way you want, move in it the way you want, and make it feel like your own. That’s what I want to communicate through Ekaya, that this is your sari and your drape. Have fun with it, break the so-called rules, and let it reflect who you are.

From a style perspective – who have been the style icons that have inspired you and the way you dress?

I'm drawn to minimalism - things that feel effortless, classic, and timeless rather than overly trend-driven. I’ve always loved Rosie Huntington-Whiteley: her style is understated yet incredibly powerful. There’s a certain restraint and confidence in the way she dresses that really resonates with me. Interestingly, I find myself looking a lot at international icons and the way they approach dressing. Women like Dakota Johnson, for instance, sometimes I’ll see her in a simple silhouette or an easy, relaxed look and immediately start imagining how that mood or sensibility could translate into something Indian. How could that same feeling exist in a Banarasi sari? How could it feel modern, effortless, and wearable, without losing its soul? That process of translation really excites me, taking a Western sensibility and reinterpreting it through Indian textiles and craftsmanship.

"Because Banarasi is such a big part of my world, I’m always subconsciously thinking about how these global references can live within that language, making the sari feel contemporary, personal, and relevant to the way women dress today."

Ekaya often sits between tradition and modern life. Do you ever feel that tension personally - between honouring legacy and wanting to stay on the pulse?

I don’t really see tradition and modern life as being in tension with each other. For me, honouring legacy actually means taking the sari forward, because a craft only stays alive when it continues to evolve and remain relevant. Banarasi weaving is an age-old, incredibly beautiful craft, and the way to honour it is by ensuring it speaks to women today and has a future tomorrow. Personally, I don’t gravitate towards overly structured or pre-conceived ways of wearing a sari: like pleated skirt saris or fixed formats. I believe a sari should remain what it has always been at its core: a piece of fabric, open to interpretation. That said, we do offer pre-stitching and pre-draping services for those who find the process intimidating or need support, because accessibility matters too. But fundamentally, I believe the sari doesn’t need to be confined or controlled. When you allow it to be fluid, expressive, and personal, you’re not moving away from tradition, you’re actually keeping it alive.

What does a sari give you emotionally that other clothes don’t? The art of draping a sari is almost like therapy for me. It’s my own quiet, personal time, something I do just for myself. While many people might see a sari as rigid or traditional, for me it’s where I feel the most free to experiment. That’s truly where I get to be my most creative self. For the longest time, I didn’t even think of myself as creative until I began to see what I could do with a sari, how a drape could change a mood, a silhouette, or the way I feel in my body. In that sense, the sari gives me something no other garment does: space. Space to explore, to play, and to reconnect with myself.

You work so closely with Banaras and its artisans - has spending time there changed how you think about pace, patience, or success?

100%. Spending time with the artisans has completely reshaped how I understand patience and success. It grounds me in a way very few things do. When you’re there, watching the process up close, you develop a deep respect for the rhythm of their work, for how long it truly takes to create something meaningful. Earlier, I’ll admit, I was far more impatient. I would question timelines, get frustrated about delays, and push for things to move faster, often without fully understanding what went into each step. But the more time I spent there, the more that perspective softened. You begin to realise that handcraft simply doesn’t operate on urgency; it operates on care. There’s only so much that can be woven in a day, only so much the loom, and the human behind it can produce.

On days when you don’t want to “perform” being a founder or creative director, what do you reach for in your own wardrobe?

On the days when I don’t like performing the role of a founder or creative director, I retreat into ease. I still love fashion, and enjoy being mildly experimental but I’m never dressing to make an announcement or command a room. For me, it’s about feeling stylish without trying too hard. More often than not, it’s something simple: a crisp white shirt and denim. But there’s always a small detail that makes it feel intentional: maybe the cut, the fit, the way it's styled, or a subtle accessory. These small elements lift my mood.

Is there a sari in your personal collection that carries a memory you’ll never part with?

It’s the very first sari I remember receiving a real compliment in. My dad helped me style it, paired with a simple white shirt, and something about that moment just stayed with me. It wasn’t about the sari alone, but about how it made me feel seen. I don’t wear it much anymore but that sari changed the game for me, it was the moment I realised how personal styling could transform how a sari feels, how it can reflect who you are rather than who you’re expected to be.

Explore Ekaya here.

For Palak Shah, the sari was never a fashion statement first - it was an environment. Growing up visiting Banaras, surrounded by looms, artisans, and generations of weaving knowledge, the sari existed as something lived-in and tactile long before it became something worn. Threads, scraps of fabric, the rhythm of handcraft - these were part of her everyday vocabulary.

That intimacy with the sari is what makes Palak’s approach feel quietly radical. Through Ekaya Banaras, she hasn’t tried to reinvent the garment - she’s simply given it room to breathe and revolutionised the relationship a modern generation has with the ancient garment. By stripping away rigid ideas of how a sari should look or be worn, she’s allowed a new generation to meet it on their own terms: fluid, expressive, and deeply personal.

In this conversation, Shah reflects on growing up inside a craft, losing and rediscovering her connection to it, and what it means to honour tradition not by preserving it unchanged - but by letting it evolve.

What’s your earliest memory of a sari - not as fashion, but as something you saw, touched, or were surrounded by growing up?

My earliest memories of a sari aren’t about fashion at all, they’re about growing up around them. I come from a family that has been involved in Banarasi saris and weaving for generations, so saris were always part of my everyday world. I remember going with my father into the narrow lanes of Banaras, walking past looms, watching artisans at work, and seeing a sari come to life thread by thread. I was especially drawn to the small fabric scraps left behind. I’d collect them and turn them into little dolls, stitching tiny outfits and creating my own imaginary worlds. That tactile connection: touching, playing, creating was probably my first real relationship with a sari.

Was there ever a moment when you personally didn’t feel connected to the sari - and if so, what changed that for you?

There was a time when I didn’t feel connected to the sari at all. I found it cumbersome, restrictive, almost distant from who I was becoming. I think that happened before I had really found my personal style, when I was still navigating what I genuinely liked versus what I felt I was supposed to like. There was a particularly clear moment I remember: walking into my own store and feeling disconnected, even thinking, I don’t like anything here. At that point, I was surrounded by very traditional saris, and while I respected them deeply, they didn’t feel like me yet. What changed everything was getting involved in the design process.

"I started creating saris the way I wanted to wear them, with a sense of ease and individuality. That’s when the sari slowly became mine."

Not something I was inheriting, but something I was actively shaping. Once I began designing for myself, the relationship shifted. The sari stopped feeling heavy and started feeling expressive. And that’s when I truly reconnected with it.

You’ve revolutionised the saree and helped make it feel wearable for a new generation. How did you have to unlearn the “rules” around wearing one?

Honestly, I don’t believe there were ever any rules to begin with. The biggest unlearning for me was simply realising that there are no rules when it comes to wearing a sari. Somewhere along the way, we’ve placed so much pressure on it: the number of pleats, how the pallu should fall, what’s considered the “right” way to drape it. At its core, a sari is just a piece of fabric, and fashion has always been about self-expression. It’s meant to be played with, experimented with, and enjoyed. You should drape it the way you want, move in it the way you want, and make it feel like your own. That’s what I want to communicate through Ekaya, that this is your sari and your drape. Have fun with it, break the so-called rules, and let it reflect who you are.

From a style perspective – who have been the style icons that have inspired you and the way you dress?

I'm drawn to minimalism - things that feel effortless, classic, and timeless rather than overly trend-driven. I’ve always loved Rosie Huntington-Whiteley: her style is understated yet incredibly powerful. There’s a certain restraint and confidence in the way she dresses that really resonates with me. Interestingly, I find myself looking a lot at international icons and the way they approach dressing. Women like Dakota Johnson, for instance, sometimes I’ll see her in a simple silhouette or an easy, relaxed look and immediately start imagining how that mood or sensibility could translate into something Indian. How could that same feeling exist in a Banarasi sari? How could it feel modern, effortless, and wearable, without losing its soul? That process of translation really excites me, taking a Western sensibility and reinterpreting it through Indian textiles and craftsmanship.

"Because Banarasi is such a big part of my world, I’m always subconsciously thinking about how these global references can live within that language, making the sari feel contemporary, personal, and relevant to the way women dress today."

Ekaya often sits between tradition and modern life. Do you ever feel that tension personally - between honouring legacy and wanting to stay on the pulse?

I don’t really see tradition and modern life as being in tension with each other. For me, honouring legacy actually means taking the sari forward, because a craft only stays alive when it continues to evolve and remain relevant. Banarasi weaving is an age-old, incredibly beautiful craft, and the way to honour it is by ensuring it speaks to women today and has a future tomorrow. Personally, I don’t gravitate towards overly structured or pre-conceived ways of wearing a sari: like pleated skirt saris or fixed formats. I believe a sari should remain what it has always been at its core: a piece of fabric, open to interpretation. That said, we do offer pre-stitching and pre-draping services for those who find the process intimidating or need support, because accessibility matters too. But fundamentally, I believe the sari doesn’t need to be confined or controlled. When you allow it to be fluid, expressive, and personal, you’re not moving away from tradition, you’re actually keeping it alive.

What does a sari give you emotionally that other clothes don’t? The art of draping a sari is almost like therapy for me. It’s my own quiet, personal time, something I do just for myself. While many people might see a sari as rigid or traditional, for me it’s where I feel the most free to experiment. That’s truly where I get to be my most creative self. For the longest time, I didn’t even think of myself as creative until I began to see what I could do with a sari, how a drape could change a mood, a silhouette, or the way I feel in my body. In that sense, the sari gives me something no other garment does: space. Space to explore, to play, and to reconnect with myself.

You work so closely with Banaras and its artisans - has spending time there changed how you think about pace, patience, or success?

100%. Spending time with the artisans has completely reshaped how I understand patience and success. It grounds me in a way very few things do. When you’re there, watching the process up close, you develop a deep respect for the rhythm of their work, for how long it truly takes to create something meaningful. Earlier, I’ll admit, I was far more impatient. I would question timelines, get frustrated about delays, and push for things to move faster, often without fully understanding what went into each step. But the more time I spent there, the more that perspective softened. You begin to realise that handcraft simply doesn’t operate on urgency; it operates on care. There’s only so much that can be woven in a day, only so much the loom, and the human behind it can produce.

On days when you don’t want to “perform” being a founder or creative director, what do you reach for in your own wardrobe?

On the days when I don’t like performing the role of a founder or creative director, I retreat into ease. I still love fashion, and enjoy being mildly experimental but I’m never dressing to make an announcement or command a room. For me, it’s about feeling stylish without trying too hard. More often than not, it’s something simple: a crisp white shirt and denim. But there’s always a small detail that makes it feel intentional: maybe the cut, the fit, the way it's styled, or a subtle accessory. These small elements lift my mood.

Is there a sari in your personal collection that carries a memory you’ll never part with?

It’s the very first sari I remember receiving a real compliment in. My dad helped me style it, paired with a simple white shirt, and something about that moment just stayed with me. It wasn’t about the sari alone, but about how it made me feel seen. I don’t wear it much anymore but that sari changed the game for me, it was the moment I realised how personal styling could transform how a sari feels, how it can reflect who you are rather than who you’re expected to be.

Explore Ekaya here.

Must Reads

Must Reads

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

Subscribe to MOLTN

© We Are MOLTN

2026

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

Subscribe to MOLTN

© We Are MOLTN

2026

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

we are MOLTN

●

Subscribe to MOLTN

© We Are MOLTN

2026